For Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), landscape is not just a representation of a piece of nature. It is also a reflection of the artist’s state of mind. To paint a landscape is to portray oneself and one’s questions. Landscape becomes a tool for self-expression.

At the start of his career, Van Gogh’s early Dutch landscapes were treated in a realistic vein. They bear as much witness to his national heritage, especially Rembrandt, as to his admiration for the painters of the Barbizon School, led by Millet.

There’s a concern for realism in the depiction of the ruined bell tower and the small cemetery that surrounds it. It’s a landscape with a heavy, sad atmosphere. This darkly colored atmosphere is reminiscent of Rembrandt’s landscapes.

During his stay in Paris between March 1886 and February 1888, Vincent discovered Impressionism and brightened up his color palette. In summer, he often went to Asnières, a town near Paris on the banks of the Seine. There he met up with his friends Emile Bernard and Paul Signac, and painted views of bridges and buildings along the river.

Both style and subject show the influence of the Impressionists. Although the restaurant is a frequent subject, Vincent is only interested in the building, whereas the Impressionist painters would have depicted the conviviality of the place. He adopted a palette of bright colors, with many touches of white. He developed the use of large parallel cross-hatching, which hints at his future style.

But it was during his stay in Arles that Van Gogh developed a very personal style. In the light of the Midi, he found the answer to his desire for an ultra-colorful palette. What’s more, he found in the landscapes everything that had fascinated him in the Japanese prints he adored. He writes that this country « seems to him as beautiful as Japan for the limpidity of the atmosphere and the effects of cheerful color ».

Van Gogh painted several versions of this drawbridge in Arles. The dynamic composition, with the canal running diagonally, draws the viewer’s eye to the bridge. The colors become increasingly vivid.

Van Gogh offers a vision of the city through a poplar curtain. The process is reminiscent of Japanese prints. The strokes become longer and longer, following the shape of the trunks.

On May 8, 1889, Vincent left Arles for the Saint-Rémy-de-Provence asylum. Allowed to paint outdoors under the supervision of a warden, Vincent developed a passion for cypress landscapes.

These moments of freedom in nature brighten his palette, which is much duller when he paints the interior of the asylum. Here, yellows are brighter, greens and blues more intense. But the skies are gradually covered with clouds, still quite calm here, but becoming increasingly tormented, reflecting his own anguish.

On May 19, 1890, Van Gogh left the asylum for Auvers-sur-Oise, where he would spend the last seventy days of his life. His activity there was intense, and seventy paintings were produced.

Here, Vincent paints a locality on the outskirts of Auvers. Behind an immense wheat field that takes up more than half the canvas, we see a group of houses, hills and a narrow strip of sky. The brushstrokes are precise and highly impastoed. They form short or long lines, dots, undulations, like the strokes of a drawing. The artist draws with color. Her colors are increasingly removed from reality. The shadow of the tree on the right becomes an undulating turquoise-blue shape. Van Gogh believes in the fortifying virtues of the countryside, and tries to convey this feeling through his painting.

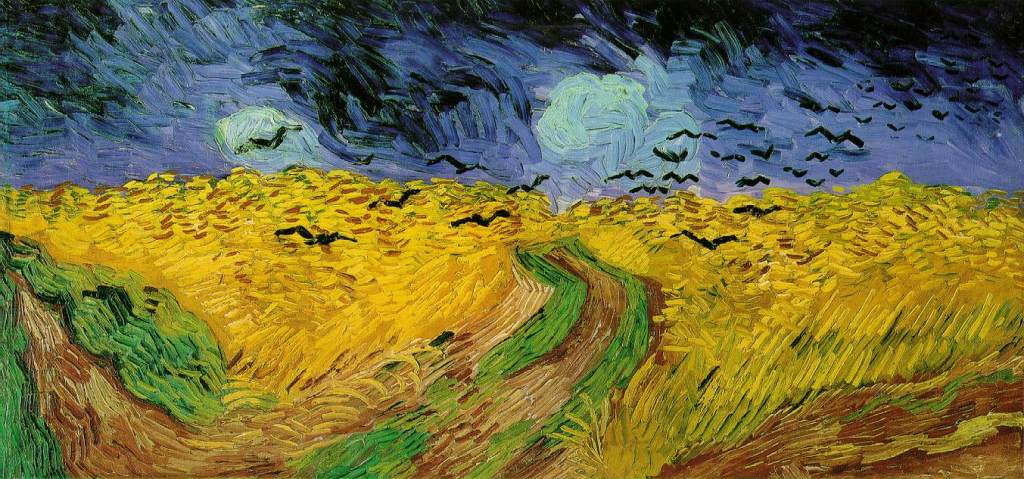

More than two stripes, one for the field and the other for the sky, are used to compose this landscape. The field is criss-crossed by three paths that disappear into the wheat. The sky, with its dark, stormy colors, is crossed by a flight of crows, an animal often associated with death. The atmosphere is eerie. Colors and shapes are implausible. Reality is distorted by the painter’s inner vision. With this landscape heralding death, Vincent reactivates his admiration for Millet, albeit in very different tonalities.

These last weeks spent in Auvers, immersed in nature, were not to save Van Gogh from depression. As in one of his last paintings, the artist found himself at the fateful crossroads that led to his suicide on July 27, 1890, in the middle of the wheat fields.